Conservatism-as-Monism; Liberalism-as-Pluralism

Abstract: I provide a brief reading of the American right/left divide, relating the conservative-right to a root in philosophical monism and the liberal-left to a root in philosophical pluralism. I further explore how pluralism relates to the problem of second-order perspectivism and offer some reflections on its political value as a discourse.

Perhaps we ought to understand the divide between right and left in America as not only an existential divide between those who want to progress and those who want to preserve, as those who stress abstract-man-as-ideal and those who revel in local-man-as-reality, but rather a distinction concerning attitudes over one’s relation to attention, openness, alterity and pluralistic engagement. I would say not only that the pluralist must assume/possess a certain attitude, but more importantly a certain well of energy that necessarily fuels a form of attentive vigilance.[1] We must start first with the reality that engagement with alterity is (usually) a demanding, exhausting effort, one that requires a certain “tough hide”[2] and a deliberate, persistent, committed strategy. Relatedly, Richard Hofstadter’s study on American anti-intellectualism is heavily instructive: like engaging the other, committing to the “life of the mind” requires a certain attitude toward labor and its relation to individual openness and self-transformation. In terms of a more general reflection on human behavior, I would say that the self-narratives we build for ourselves[3] are, due to our closeness to our own daemon, always askance our objectivity, or the ways we are perceived by others; of course, we may try to close this gap by inhabiting various angles of second-order perspectivism, but these efforts are always limited, as they spring from the very source from which they are destined to return. That we cannot “know ourselves” but through others means, too, that we are forced to therefore fill in certain holes, manufacture and live by certain self-illusions, some healthier and more socially permissible than others.

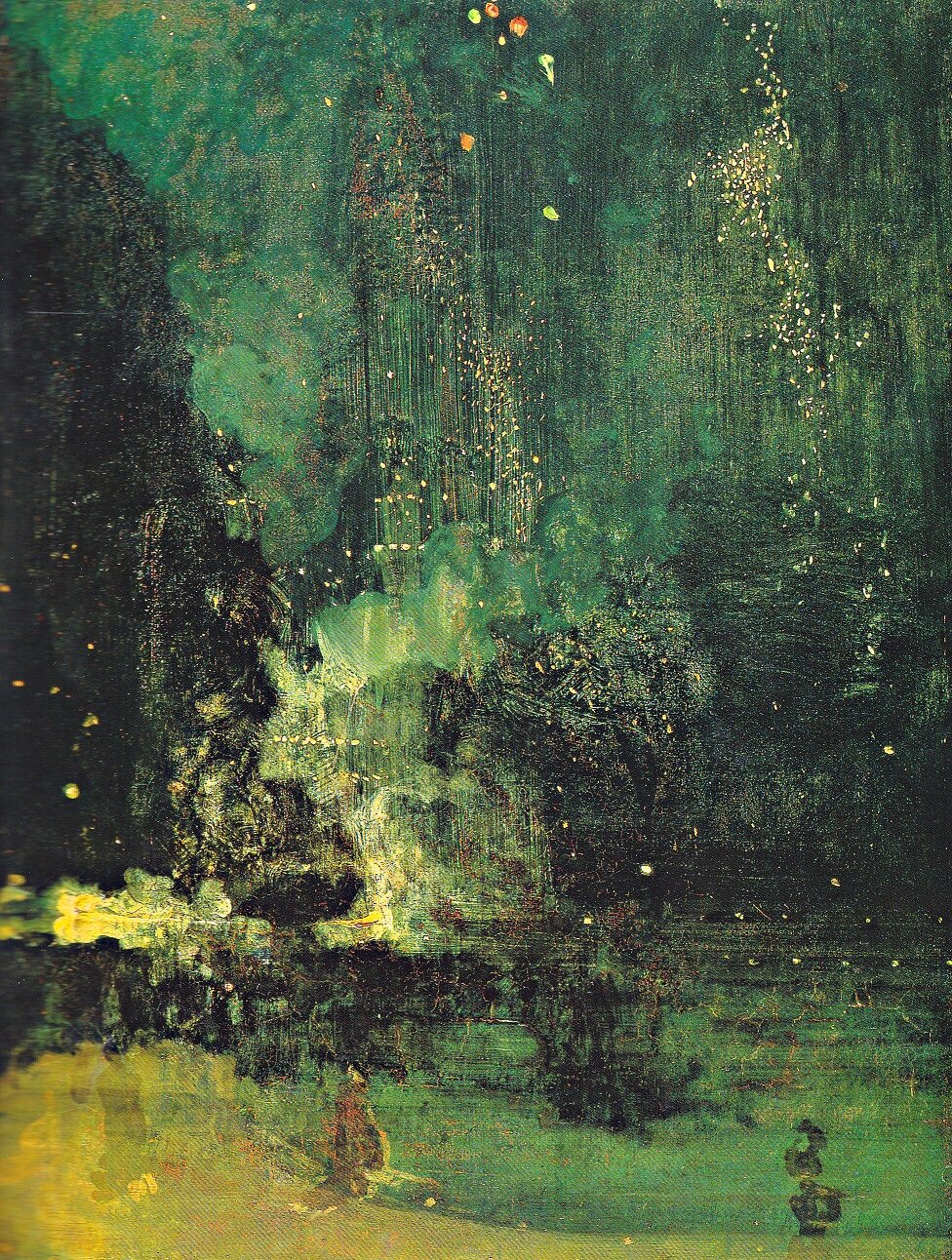

This reminds me of one of the things that has struck me most in my early reading of Paul Hazard’s Crisis of the Modern Mind.[4] I am interested in the role by which travelers/travel logs, and by extension the trope and aesthetic category of the “exotic,” with its auras of mystery and unknowability, acts as a persuasive frame of reference on the early modern European mind. The role of anecdotes hold special force in this setting, where doubt is not so much suspended, as it is first never given a stable frame in which to operate.[5] That is, it seems to me that, with the right details, a traveler from a distant land could come back telling tales of virtually anything—magic peoples, legendary chimera, blood-sunsets and emerald mist-borealises—and who would be there to “fact check,” to counteract or question or challenge? Much seems permitted in this extensive sphere of the unknown: I think, too, of the explosion of utopian travel narratives, and the trope of illustrating ideality-through-distant-lands.

But it is the status of the exotic that also provides some political import,[6]and which leads me to reflect on the desire for a people (and by conceptual extension, oneself) to sidestep the daemon and seek judgment through the creation of a second-order perspective—manifest in the broad darkness of exotic alterity. Or: where there is no mirror, there is at least the desire for one. I am reminded of the trope of Snow White’s “Mirror, Mirror, on the wall…”—while we desire to see perfection, it is equally a human trope to 1. Desire judgment, even in its masochistic, negative form; and 2. To project, e.g. invent, perfection where it does not exist—Dorian Gray in negative, or, quite simply: narcissism. The desire for this mirror, which also paralleled the growth of individualism itself and which fragmented into the “Mirror of Princes” literature,[7] was born in the international travel writing and colonial efforts of the 17th century.[8] The irony of medieval travel-log utopias is that they produced visions of idealistic monism which were undermined by the very multiplicity and popularity of depicted elsewheres; so while we see the growth in utopian literature, this is reflected not by a dramatic dominance of monistic thinking, but rather the opposite—we see the spread of doubt vehicled by the experience of a new type of pluralism.[9]

Exoticism thus seems to inspire and ultimately favor a politically-progressive and socially-critical attitude—one which will find its formal theoretical grounding first in the critical-utopian moment of Hegel, then Marx, and finally the Frankfurt effort.[10] This involves a combination of a novel type of wonder and admiration with the recognition of irreconcilable differences.[11] Thus we ought to map out how exoticism’s relation to escapism is further linked to the development and spread of skepticism.

Finally, I am lead to consider how the development of sociology in the late 19th-century paralleled the emergence of colonial studies and anti-colonial movements; to this end, the colonial project did not only provide the European mind with the civilized/uncivilized discourse which would link Arthur Lovejoy’s notion of the “great chain of being” to Mill’s notion of the hierarchical staging/nature of history (and hence enable entire fields of sociological research to emerge viz. this exoticized “otherness,” by which the European could come to see his/her own practices as embellishments and evolutions of “primitive” structures/forms—think the trope of “Maslow’s hierarchy of needs”), but also with the theoretical framework of alterity by which to construct the European daemon. Or: colonialism was a technique of oppression that not only imposed European identity, but negotiated it, served to showcase its point of fracture and contradiction. I would in fact say: the more the European identity imposed itself, the more it revealed its own insecurity, instability and incompleteness. Or: insecurity wracks nations as it does individuals.

Here’s an odd—but related—utopian/dystopian thought-experiment that illustrates an aspect of this second-order perspectivism: imagine a world in which one’s soul or consciousness is born not into one’s own body (e.g. a material body that is under one’s own volitional/mental control), but the body of another—that you see out of the eyes of a body you do not control, just as others do the same. Each material form is thus subject to another’s volition: one does not so much have a doppelganger as he/she has a linked owner and a linked ownee. What I envision is something between Borges’ “Circular Ruins” and the widely-circulated, popular parable of heaven and hell that illustrates both as an endless feast, with feasters equipped with cutlery that is three feet in length, thus able to reach the mouths of others but not able to feed those who hold them—those in heaven know not want, while those in hell know only want. I think, too, of combining Borges’ prophet-visionary-manmaker with Rawls’ conception of the “veil of ignorance”: that is, if you knew you were to be imagined by someone else, how would you imagine another in turn? I wonder if we would suffer from the same societal ills and political calamities under such conditions, where there is a “forced-to-be-free” principle[12] embedded in this naturalized “forced-to-second-order-perspectivize,” where Arendt’s notion of the daemon becomes an explicit, embodied political phenomenon.

The overarching point, however, is that encounters with the other have the potential to disclose the fabricated nature of our self-illusions, thus rendering them, to attitudes accustomed to non-reflection, fairly inert and insubstantial—outside of a controlled thought-experiment, we end up blaming the other for inadvertently illuminating an area of our own insecurity or dissimulated reality. Here is the structural equivalent of “shooting the messenger,” taken in the context of ethics and morality—Socrates’ policy of returning to the cave is perhaps the ideal-model for this type-of problematic. This we might call not a worldview-monism, but a personal-monism, the other half of the foundation of xenophobia, homophobia, racisms, sexism, etc. I would say that worldview- and personal-monism must always work in tandem, but it is important to distinguish the two: anger directed toward the other, the perceived labor in engaging the other, may often come about viz. the idea of a single, authentic, monistic self, one that is cohesive and coherent, despite the necessary violence perpetrated against reality involved with the creation of self-illusion. The xenophobe hates the foreigner not only because the foreigner threatens a worldview, a material place within that worldview, etc., but also because the foreigner threatens a coherent illusion of a naturally splintered and paradox-laden self: when one is a monist, one is a monist through and through, so to speak—one is a monist “all the way down,” not just politically, but personally—James and Berlin the vanguard of this perspective.

We must therefore see the American right/left cleavage not only as a struggle between the will to preserve and the will to alter, but as an active engagement with the pluralistic world and a will to find reprieve from it, to not engage dynamism and disruption, to offload certain psychological and emotional costs.[13] This offloading we call bias/prejudice, and it always has the air of a tired ressentiment about it—not a laziness, per se, but a rejection of a certain form of self-labor or communal work.[14] This is not to say that conservatives in America are strictly monists—though many certainly exhibit some form of monism or another; rather, it is to say that many are committed anti-pluralists, or pluralists of a strict and narrow (and hence pseudo-) kind[15]—they lack a fully-fledged positive doctrine but know with certainty the foreigners that don’t belong. To this end, adjudicating who should stay and who deserves deportation, without a consistent lodestar, is ironically part of modern conservatism’s self-structured paradox: its embrace of a quasi-monism is just sloppy enough to open the space not for formal programs or institutions (and, of course, this would signal its own problems), but for the rise of (what will no doubt prove uncontrollable) plebiscitary/crowd politics.

[1] See David Foster Wallace on liberal education and regimes of attention; Grant McCracken on encounters with the other, and under what conditions these encounters become laborious.

[2] See William James on the type of attitude necessary to live amidst pluralism; Nietzsche, Gay Science #124; also, see my notes on love (8.35) and the attitude required to love openly, pluralistically, polyamorously.

[3] I have here Arendt in mind; see, too, Iris Maria Young and Charles Tilly on story-telling.

[4] In reference to the following reflection on Hazard, see p. 10 of Crisis.

[5] See Paul Fleming.

[6] See Hazard, Crisis, p. 14.

[7] See Gracian, Machiavelli, Guicciardini; see, further, Burkhardt on Renaissance Italy.

[8] See Eugen Weber, Peasants into Frenchmen, p. 489.

[9] See Hecht, Wittgenstein, James.

[10] For commentary on this trajectory, see Seyla Benhabib, Critique, Norm, and Utopia; Stuart Jeffries, Grand Abyss Hotel.

[11] See Hazard, Crisis, p. 16.

[12] See Rousseau.

[13] See Marcuse; Hoffer.

[14] See the problem of the “moral economy”: Augustine, Aquinas, Locke and Marx are the principle theorists/trajectory here.

[15] See Bernard Williams’ essay, “Democracy and Ideology.”